It’s something that was the dream of science fiction writers even before the dawn of computing, the concept that human beings could invent machines that would mimic or even surpass our intelligence and become part of our daily lives, the quotidian. To many, this still seems a far-fetched notion, but look around: artificial intelligence is already part of everyday life. 1950s AI engineers Marvin Minsky and John McCarthy defined artificial intelligence as anything a computer or machine does that we would say a human would need to use their intelligence to replicate. When you talk to Alexa, call up a list of recommendations on Spotify, or ask Siri to give you directions, you’re asking a machine and a computer program to accomplish something that humans would need to apply intelligence to accomplish.

Researchers tend to divide AI into two forms, narrow AI and general AI (or Artificial General Intelligence, AGI). Narrow AI is effectively what we already have, machines that can accomplish specific tasks that would require human intelligence, e.g. guiding a driverless car. AGI is what is to come, and if it does develop as predicted it would involve machines that could, like humans, turn their hand to any task, learning as they go and applying past experience to make sense of new challenges.

Such forms of AGI are still some way off; however, surveys of experts in the field have revealed a general consensus (in those who believe it will happen at all, see below) that there is a 50-50 chance of true AGI being available by 2050, and a 90% chance of it arriving by 2075. Some researchers have even predicted that 30 years after arriving at AGI, computers will have developed “superintelligence”, whereby they will greatly outstrip the capacity of human intelligence. Welcome to Skynet, how can I help you today? Even more (and literally) mind blowing, some researchers have predicted the development of AGI modules that could be plugged in to enhance the human brain, effectively turbocharging human intelligence.

Many of these predictions are predicated on our capacity to develop neural networks. These are enormously complex computer systems that effectively mimic the human brain and its ability to amass data, collate it and apply its most relevant learning to any task it is given. Sceptics point out that at present we only really understand about 10% of the workings of the human brain, thereby making it impossible to create computers that can replicate it; enthusiasts contend that as our computers become more sophisticated, they will help us gain a deeper understanding of the human brain, which will in turn help us build more sophisticated computers.

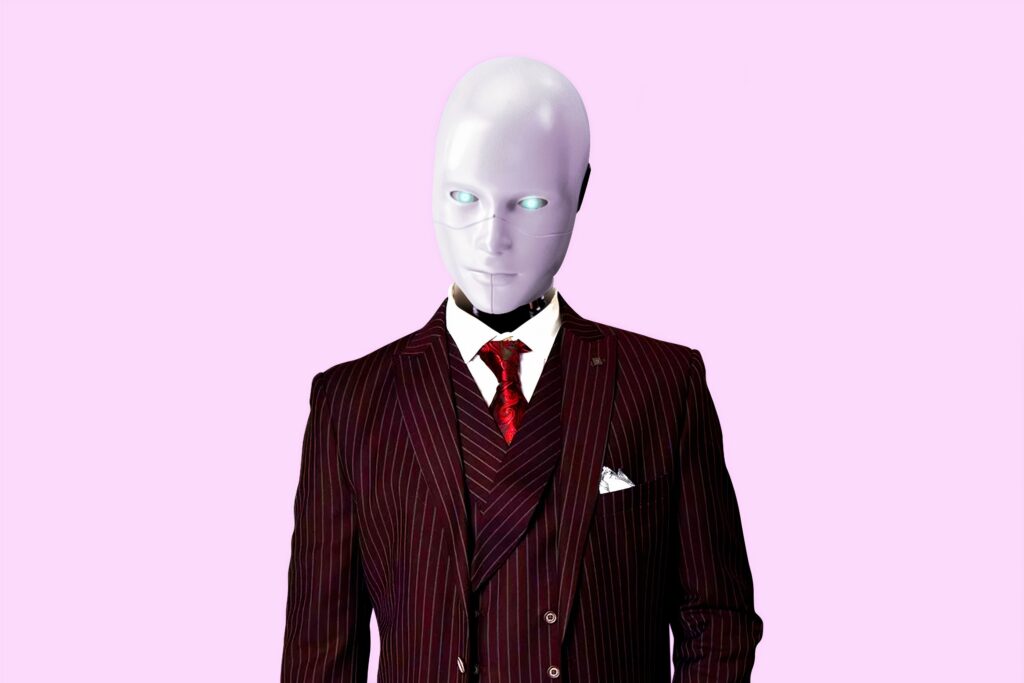

The moral, ethical, and legal implications of the development of true AGI are clearly immense. How much control should we hand over to computers? At present (supposedly, though if one looks at our current leaders one might doubt it) society generally works on the premise that the most intelligent will enjoy the greatest success. If we have fully functioning AGI computers more capable and intelligent than the most intelligent human, what will be their position in society? AGI computers and robots could accomplish any human work tasks better than humans themselves; what are we going to do with all the employees who’ve been put out of work? Will we enjoy a life of unparalleled leisure, waited on hand and foot by AGI servants, or will we become the irrelevant slaves or pets of our AGI overlords? In many ways these questions are unanswerable; perhaps one day we’ll invent a computer intelligent enough to answer them for us.